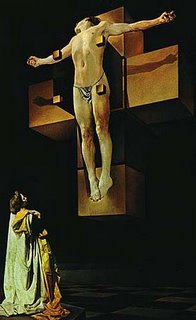

It's the obvious hymn--but as with most hymns, a reading (and singing) of all the verses rewards such close attention. See how the song calls us to a heavenly host, a marching-song, as it were, even as the Church Militant becomes the Church Triumphant. And we sing, as the King of Glory passes on His way!

It's the obvious hymn--but as with most hymns, a reading (and singing) of all the verses rewards such close attention. See how the song calls us to a heavenly host, a marching-song, as it were, even as the Church Militant becomes the Church Triumphant. And we sing, as the King of Glory passes on His way!For all the saints, who from their labors rest,

who thee by faith before the world confessed,

thy Name, O Jesus, be forever blessed.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

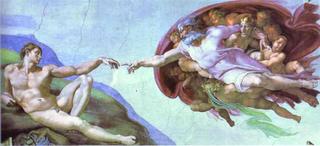

Thou wast their Rock, their Fortress and their Might;

thou, Lord, their Captain in the well fought fight;

thou, in the darkness drear, their one true Light.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

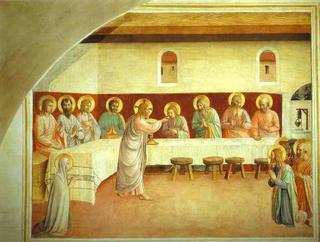

For the apostles' glorious company,

who bearing forth the cross o'er land and sea,

shook all the mighty world, we sing to Thee:

Alleluia, Alleluia!

For the Evangelists, by whose blest word,

like fourfold streams, the garden of the Lord,

is fair and fruitful, be thy Name adored.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

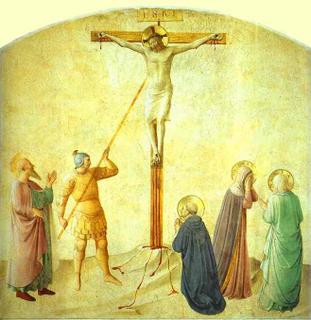

For Martyrs, who with rapture kindled eye,

saw the bright crown descending from the sky,

and seeing, grasped it, thee we glorify.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

O may thy soldiers, faithful, true, and bold,

fight as the saints who nobly fought of old,

and win, with them the victor's crown of gold.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

O blest communion, fellowship divine!

we feebly struggle, they in glory shine;

all are one in thee, for all are thine.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

And when the strife is fierce, the warfare long,

steals on the ear the distant triumph song,

and hearts are brave, again, and arms are strong.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

The golden evening brightens in the west;

soon, soon to faithful warriors comes their rest;

sweet is the calm of paradise the blessed.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

But lo! there breaks a yet more glorious day;

the saints triumphant rise in bright array;

the King of glory passes on his way.

Alleluia, Alleluia!

From earth's wide bounds, from ocean's farthest coast,

through gates of pearl streams in the countless host,

and singing to Father, Son and Holy Ghost:

Alleluia, Alleluia!

This coming New Year's Eve, a fantastic way to celebrate the New Year is the gorgeous Mozart at 250 at St James Cathedral in Seattle.

This coming New Year's Eve, a fantastic way to celebrate the New Year is the gorgeous Mozart at 250 at St James Cathedral in Seattle.