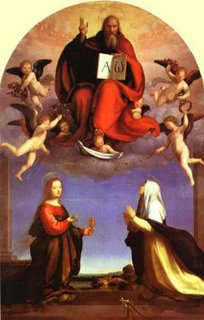

It is the most beautiful, most profound thing written on Love since Plato's Symposium; and it surpasses Plato, because it identifies Love with the God who has come to us in Jesus Christ.

It is the most beautiful, most profound thing written on Love since Plato's Symposium; and it surpasses Plato, because it identifies Love with the God who has come to us in Jesus Christ.

Exploring the Truth Goodness and Beauty of God in art, music, poetry, literature and the prayer-life of the Roman Catholic Liturgy

Thursday, January 26, 2006

The Beauty of Love

It is the most beautiful, most profound thing written on Love since Plato's Symposium; and it surpasses Plato, because it identifies Love with the God who has come to us in Jesus Christ.

It is the most beautiful, most profound thing written on Love since Plato's Symposium; and it surpasses Plato, because it identifies Love with the God who has come to us in Jesus Christ.

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

Stigma, Signal, Cinquefoil Token for Lettering

So now Hopkins gives us a long meditation on that Tall Nun, from stanza 19 through stanza 31. This is very much the climax of The Wreck of the Deutschland.

So now Hopkins gives us a long meditation on that Tall Nun, from stanza 19 through stanza 31. This is very much the climax of The Wreck of the Deutschland.Stanza 19 introduces the theme: “Sister, a sister calling/A master, her master and mine!”

Here the Tall Nun is identified, and she calls out even against the storm. Thus our life of Faith is often opposed by the world; it doesn’t take a storm for us to know persecution, though it may take a storm to remind us. Saints and Martyrs provide us, by the romantic, sublime exaggeration of extreme and heroic virtue against the storms of this world’s life, a drama of inspiration. So too does this Tall Nun. And she is pure of heart, authentically directed, well-oriented: “But she that weather sees one thing, one;/ Has one fetch in her.” One fetch!

Stanza 20—“She was first of a five”—gives us the Religious Order of the nuns but at once meditates on the name of the ship and the homeland—“Deutschland”—by ironically juxtaposing St Gertrude & Martin Luther. So here we have a slam broadminded ecumenists would avoid and Lutherans should resent! But while we don’t want to do cartoon history and do to the Protestants what Schiller did to Catholics in Don Carlos, yet we can perhaps see in the juxtaposition of the two Germans, the “lily” and the “beast” a comment on two ways of life—the former, the committed & authentic & vowed life of the Evangelical Counsels, a true Gospel life; and the latter, the renegade, the rebel, the revolutionary. “Lily”, of course, reminds us of both Easter and virginity. “Beast”, beyond the obvious, reminds us of the three beasts “of the waste wood” of darkness and error at the start of Dante’s Comedy—three bestial roots of sin, to be compared to and countered by the three Evangelical Counsels of the Gospel lifestyle of Chastity, Poverty, and Obedience. Here, again, Hopkins is reminding us that his poem is also about the journey of modern Europe—the voyages to America and the revolt of Luther being flipsides of the same story, the breakdown of Christendom. And Hopkins sees this modern story for what it is in theological terms—sin. “From life’s dawn it is drawn down . . .Abel . . .Cain.” Then there is a final image of sucking on breasts. Yes, I know it means Cain & Abel were both babies of Eve, but we cannot help but see the sucking on breasts as an odd, deliberately evocative image in a stanza focused on the authenticity of the Nun. It is a healthy reminder too that the Evangelical life of the Nun does not reject the body, sex, breast-sucking, baby-making, or human culture as bad in themselves—quite the contrary.

Stanza 21—“Loathed for a love”—traces the event of the nuns’ exile in terms both historical and theological. Hopkins links the Hun’s experience of Bismark’s persecution of the Church to the Passion and Sacrifice of Christ. Again, Hopkins theologically sees the whole thing in terms of Love: “Loathed for a love men knew in them” . . .and . . .”They unchancelling poising palms.” And while human eyes would see the sstorm as a storm, Hopkins sees the snow and ice and wind as “scroll-leaved flowers, lily showers.” Once again, God is termed, as before for both the poet’s heart and the Tall Nun, as “Master”, but now “Martyr-master.”

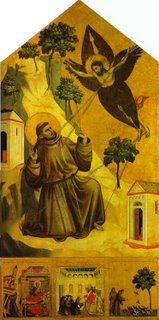

And this theme continues in stanza 22—“Five!”—in identifying the Five Nuns with the Five Wounds of Christ. This stanza is particularly beautiful, especially in the litany—“Stigma, signal, cinquefoil token for lettering . . .ruddying.” No comment can improve the beauty of these lines, but one ritual perhaps reveals them—the stabbing of the Paschal Candle with the five grains of incense signifying Christ’s “holy & glorious wounds”. The phrase “and the word of it Sacrificed” has a direct parallel in form and position to a phrase in the next stanza: “Lovescape crucified.” This next stanza, #23, continues the whole theme with a meditation on the Stigmata of St Francis.

Sister, a sister calling

A master, her master and mine!—

And the inboard seas run swirling and hawling;

The rash smart sloggering brine

Blinds her; but she that weather sees one thing, one;

Has one fetch in her: she rears herself to divine

Ears, and the call of the tall nun

To the men in the tops and the tackle rode over the storm’s brawling.

She was first of a five and came

Of a coifèd sisterhood.

(O Deutschland, double a desperate name!

O world wide of its good!

But Gertrude, lily, and Luther, are two of a town,

Christ’s lily and beast of the waste wood:

From life’s dawn it is drawn down,

Abel is Cain’s brother and breasts they have sucked the same.)

Loathed for a love men knew in them,

Banned by the land of their birth,

Rhine refused them. Thames would ruin them;

Surf, snow, river and earth

Gnashed: but thou art above, thou Orion of light;

Thy unchancelling poising palms were weighing the worth,

Thou martyr-master: in thy sight

Storm flakes were scroll-leaved flowers, lily showers—sweet heaven was astrew in them.

Five! the finding and sake

And cipher of suffering Christ.

Mark, the mark is of man’s make

And the word of it Sacrificed.

But he scores it in scarlet himself on his own bespoken,

Before-time-taken, dearest prizèd and priced—

Stigma, signal, cinquefoil token

For lettering of the lamb’s fleece, ruddying of the rose-flake.

Joy fall to thee, father Francis,

Drawn to the Life that died;

With the gnarls of the nails in thee, niche of the lance, his

Lovescape crucified

And seal of his seraph-arrival! and these thy daughters

And five-livèd and leavèd favour and pride,

Are sisterly sealed in wild waters,

To bathe in his fall-gold mercies, to breathe in his all-fire glances.

Lovescape Crucified!

Sunday, January 15, 2006

The Habit of Perfection

We are pausing at the middle of The Wreck of the Deutschland to consider Hopkins’ vision of the response to the religious Call. And we have been taking a look at earlier poems on this theme—such as Heaven-haven and Halfway House.

We are pausing at the middle of The Wreck of the Deutschland to consider Hopkins’ vision of the response to the religious Call. And we have been taking a look at earlier poems on this theme—such as Heaven-haven and Halfway House.And a third early poem comes to mind, while we contemplate the Tall Nun, and while we consider the mystery of The Wreck’s stanza 18—another hymn, perhaps, about a girl joining a convent or a young man joining the priesthood—“The Habit of Perfection.” It’s a gloss on St Augustine’s transfiguration of the senses in “Too late have I loved Thee, O Beauty ever ancient ever new, too late have I loved Thee.” In St Augustine’s beautiful paragraph, each of the five senses is given its full due—touching, hearing, seeing, tasting, even smelling—in full acceptance of the rich sensuous Beauty of the sensation, and then each of the five senses is drawn up towards the source of all Beauty, God. Hopkins’ gloss here is indeed full of the same old, new anarchy of images, of paradox, of contradiction, so fitting for a crux:

ELECTED Silence, sing to me

And beat upon my whorlèd ear,

Pipe me to pastures still and be

The music that I care to hear.

Shape nothing, lips; be lovely-dumb:

It is the shut, the curfew sent

From there where all surrenders come

Which only makes you eloquent.

Be shellèd, eyes, with double dark

And find the uncreated light:

This ruck and reel which you remark

Coils, keeps, and teases simple sight.

Palate, the hutch of tasty lust,

Desire not to be rinsed with wine:

The can must be so sweet, the crust

So fresh that come in fasts divine!

The “can” is the Tabernacle, by the way; the “crust” is the Blessed Sacrament, as in the much later poem, similarly a hymn to Beauty, “The Bugler’s First Communion”: “Forth Christ from cupboard fetched, how fain I of feet/To his youngster take his treat!” Back now to the poem, almost vulgarly to nose & toes:

Nostrils, your careless breath that spend

Upon the stir and keep of pride,

What relish shall the censers send

Along the sanctuary side!

O feel-of-primrose hands, O feet

That want the yield of plushy sward,

But you shall walk the golden street

And you unhouse and house the Lord.

Here I imagine Hopkins imagines himself a Priest who takes and puts the Blessed Sacrament into and out of the Tabernacle. And finally, total simplicity; abject simplicity—and here both Schubert’s Winterreise and Eliot’s Four Quartets can join in :

And, Poverty, be thou the bride

And now the marriage feast begun,

And lily-coloured clothes provide

Your spouse not laboured-at nor spun.

Re-read these three earlier poems—“Heaven-haven” and “The Half-way House” and “The Habit of Perfection”—as a study for the contemplation of The Deutschland’s contemplation of the Tall Nun and the mystery at the heart of its 18th stanza—and so much then becomes clear, indeed rich, indeed One and True and Good and Beautiful!

Thursday, January 12, 2006

Half-way House

And another, slightly later poem comes to mind: “The Half-way House” Hopkins, who has desired to go to a place where springs do not fail—in so many senses—and where not storms come—in a prophetic vision of The Deutschland’s wreck—Hopkins finds himself halfway there in this early poem, on a journey urged by Love:

And another, slightly later poem comes to mind: “The Half-way House” Hopkins, who has desired to go to a place where springs do not fail—in so many senses—and where not storms come—in a prophetic vision of The Deutschland’s wreck—Hopkins finds himself halfway there in this early poem, on a journey urged by Love:“Love I was shewn upon the mountain-side

And bid to catch Him ere the drop of day.

See, Love, I creep and Thou on wings dost ride:

Love, it is evening and Thou away;

Love, it grows darker here and Thou art above;

Love, come down to me if Thy name be Love.”

Here, the Road to Emmaus is combined with Tristan & Isolde, with Romeo & Juliet. The religious road is perhaps first an erotic road. Hopkins, the homosexual Oxford student, is on a journey of Love whose “local habitation and a name” he yearns for and has yet to know. But he does see his journey from Protestant English heresy through Oxford Tractarianism toward Rome as a Paschal escape from Egypt:

“My national old Egyptian reed gave way;

I took of vine a cross-barred rod or rood.

Then next I hungered: Love when here, they say,

Or once or never took Love’s proper-food;

But I must yield the chase, or rest and eat.—

Peace and food cheered me where four rough ways meet.”

What a journey Hopkins was on! No wonder he later so sympathized with the Tall Nun and her Sisters on The Deutschland’s journey and wreck! And the “four rough ways” do meet at a crossroads—the Cross-Road, the Way of the Cross, the moment of the Cross, the Crux of the Cross. See how these earlier poem’s elucidate the mystery at the heart of The Wreck of the Deutschland’s stanza 18! And then, Hopkins, as he does in “Part the First” of the later poem, sees the guide for his journey, the compass-point of his love’s confusion and sense of loss, his north pole in the Host, in the Real Presence of Our lord Jesus Christ in the Eucharist:

“Hear yet my paradox: Love, when all is given,

To see Thee I must see Thee, to love, love;

I must o’ertake Thee at once and under heaven

If I shall overtake Thee at last above.

You have your wish; enter these walls, one said;

He is with you in the breaking of the bread.”

God! How stunning, gorgeous, beautiful is Hopkins’ vision! Here, here is the clue to the meaning we avoid! Here is the key to the mystery of The Wreck’s stanza 18: it’s in the “Lovescape crucified!”

Wednesday, January 11, 2006

Heaven-Haven

“Sister, a sister calling

A master, her master and mine!”

These words do sound like Music, even like a madrigal, as promised in the previous stanza’s request for “a madrigal start!”

Here we might pause and remember some earlier poems of Hopkins, poems about the Call, the Response, the yearning for Peace, the erotic desire for a religious life—earlier poems that might shed some light on the mystery of stanza 18 of The Wreck of the Deutschland and on the Voice of the Tall Nun.

Here’s one: Heaven-haven—a nun takes the veil. The fact of the character of a Nun and the reference to a Haven (“Bremerhaven”) reminds me of The Wreck of the Deutschland.

“I have desired to go . . .”

It is the expression of a yearning to go on a journey—a strange link between the chaste longing of a sister entering the convent and the Wagnerian Sehnsucht of Tristan. Hopkins, after all, is a Romantic poet!

“I have desired to go

Where springs not fail,

To fields where flies no sharp and sided hail

And a few lilies blow.”

The reference to lilies reminds me of the fragrance of the lilies in the poetry of St John of the Cross (also contemplated by Balthasar in his Theological Aesthetics), especially On a Dark Night: “ . . .and rest my cares amongst the lilies there.”

“And I have asked to be

Where no storms come,

Where the green swell is in the havens dumb,

And out of the swing of the sea.”

Tristan similarly sings an invitation to Isolde to follow him to a land where the sun shines not. Hopkins penned this Tristanesque lyric as a young man of twenty, while at Oxford, while an Anglican in the midst, like the boy Jesus in amidst the doctors in the Temple, of Walter Pater, Benjamin Jowett, Edward Pusey, Swinburne, Solomon, and John Henry Newman. The meaning is quite clear.

The journey to God is a journey of an erotic desire, from storm to haven, from swelling sea to silent home, from sharp and sided hail to a land of fresh springs and the fragrance of beautiful flowers—that journey of Eros toward the Truth and Goodness and Beauty of God.

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

St Basil on Beauty

In praise of the Beauty of God, this passage sings, today, from the Office of Readings—a selection from St Basil the Great:

“What, I ask, is more wonderful than the beauty of God? What thought is more pleasing and satisfying than God’s majesty? What desire is as urgent and overpowering as the desire implanted by God in a soul that is completely purified of sin and cries out in its love: I am wounded by love? The radiance of the Divine Beauty is altogether beyond the power of words to describe.”

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Her Voice, Her Heart, Hermeneutics

Beginning with the appearance of the Lioness and remaining until stanza 31, which is the start of the final doxology, the poem The Wreck of the Deutschland stands still in eloquent contemplation of the Tall Nun and her Voice!

Beginning with the appearance of the Lioness and remaining until stanza 31, which is the start of the final doxology, the poem The Wreck of the Deutschland stands still in eloquent contemplation of the Tall Nun and her Voice!Stanza 18 is almost a tease, a clever Oxford-common-orom chat. The poet has already addressed the “lioness” and the “prophetess”—and now he calls her a “heart” at the same time. But he teases us—no, he’s not addressing the Nun only but also his own heart: thus the seemingly flippant manner, so wildly seemingly inappropriate for the storm, the wreck, and the martyrdom, but still iconic of holy wit: “Ah, touched . . .are you! Turned . . .have you! Make words . . .do you!” The link, of course, between the Nun and his heart is the man-woman relationship both within the created human personal soul—each person as a person sharing in the fundamental androgyny of humanity, split by gender into Eve & Adam—and between God and the person —we all being feminine before the divine masculine. (This interior androgyny, with reason and imagination, with an interior father and interior mother, is well explored in Hopkins’ poem dedicated to Robert Bridges, “To R.B.”) This whole stanza is particularly dense and difficulty, seemingly unfitting to the context—a witty puzzle juxtaposed to the tragic tale and the invitation to “a madrigal start.” And one of the phrases is seemingly inexplicable—“O unteachably after evil”—perhaps Hopkins referring to his own sinfulness, or at least the moral ambiguity of his poetry-making in his own eyes. But the ambiguity of what the text means at all is predominant: the words all through could refer both to the Nun and also to the poet—linked at “mother of being in me, heart”. The poet expresses an alarm, a surprise that causes both tears and a madrigal: something pent up is being release: “ . . .such a melting, a madrigal start!/Never-eldering revel and river of youth,/What can it be, this glee? The good you have there of your own?”

Perhaps we might unlock the puzzle of this dense stanza (and the whole poem) if we remember that it is telling a tale on three levels---

---the literal tale of the actual wreck of the ship The Deutschland, and the drowning of the Nuns, and the heroic call of the Tall Nun

---the allegorical tale of modern Europe, of the West in wreck, of Germany in particular as the country of rebellion against God, of the attempt to destroy the Church, of the witness of modern Christians

---the moral tale of the interior life of Hopkins the poet himself, both as an artist and as a Christian, which seems to be most of all the poem’s concern, given the lengthy Part One which is a Principle and Foundation of the Spiritual Exercises of the whole

And to this we might add (though not fully yet, because we haven’t finished reviewing The Wreck of the Deutschland in detail) there is a fourth level—an analogical level, which draws the literal story, the allegory of the West, and the personal moral spirituality, all up, up, up into the revelation of the Heavenly reality of the inner life of God the Holy Trinity.

I do think Hopkins indeed intended all these levels, and stanza 18 is the real heart of the puzzle. Perhaps this is best demonstrated by the fact that stanza 18, this enigmatic crux of the poem, is actually the central stanza between stanza 1 and the final stanza 35. No wonder it is a mystery, a question, a strangeness, the place of the intersection of all the ways of reading the poem. It’s the one place in the poem where we don’t really know where we are, where, who, how, what, or when we are. It is the crux of the analogous imagination. And—to risk more complexity—it’s the moment when the poet actually speaks of being so moved as to pen a poem, to utter and to arrange utterances.

Ah, touched in your bower of bone

Are you! turned for an exquisite smart,

Have you! make words break from me here all alone,

Do you!—mother of being in me, heart.

O unteachably after evil, but uttering truth,

Why, tears! is it? tears; such a melting, a madrigal start!

Never-eldering revel and river of youth,

What can it be, this glee? the good you have there of your own?

Tuesday, January 03, 2006

The Sailor & The Nun

In stanza 16, “One stirred”, a brave, generous-hearted sailor tries to save the women, is blown and thrown off the ship, and is swung by a rope in the storm. The horror of the remaining passengers “could tell him for hours, dandled the to and fro.” Perhaps a type of Christ, not that he saved them (because he didn’t) but that he sacrifices himself trying to.

The rhetoric of stanza 17 reminds me of “A voice cries out in Rama—Rachel weeping for her children—and she could not be consoled—because they were not.” That’s the effect, in sound and meaning, of fighting with God’s cold, “and they could not and fell to the deck”, and “crushed them” and “drowned them” and “the crying of child without check”.

All this till a brave Tall Nun, a Franciscan, daughter of St Clare, rises up in the darkness of the night, out of this cinematic storm!

“Till a lioness arose breasting the babble/A prophetess towered in the tumult, a virginal tongue told.”

One can almost hear music at this moment: we are not at first aware that the heroine now is the Nun. I suppose we are presumed to know the story already: but nowadays no one does except readers of Hopkins’ poem. It’s like those moments in Titanic when well-known incidents are suggested (the husband & wife drowning, willingly, in bed together, for example). But either way, we’ll know she’s a Nun soon enough. More than enough for now, we see “a lioness” . . .”a prophetess” . . .a tower . . .and “a virginal tongue told”.

Thus suggested too are the Virgin Mary, Judith, Esther, Deborah. In fact, is it not amazing that the figure of Woman in the biblical tradition is not ever a priestess but rather a Judge, a Warrior, a Prophetess, as a figure of the People of Israel?!? In fact, the whole Litany of the Virgin Mary, with its Tower and City and Queen, is in praise of this heroic Woman.

And up she rises, this Tall Nun, this Tower, this Lioness . . .and now, time will stop for several stanzas as we meditate on this Woman.

One stirred from the rigging to save

The wild woman-kind below,

With a rope’s end round the man, handy and brave—

He was pitched to his death at a blow,

For all his dreadnought breast and braids of thew:

They could tell him for hours, dandled the to and fro

Through the cobbled foam-fleece, what could he do

With the burl of the fountains of air, buck and the flood of the wave?

They fought with God’s cold—

And they could not and fell to the deck

(Crushed them) or water (and drowned them) or rolled

With the sea-romp over the wreck.

Night roared, with the heart-break hearing a heart-broke rabble,

The woman’s wailing, the crying of child without check—

Till a lioness arose breasting the babble,

A prophetess towered in the tumult, a virginal tongue told.

Monday, January 02, 2006

Into the snows she sweeps . . .

The Deutschland plunges into the North Sea. The overall atmosphere, as at the beginning of Hamlet, is cold and unkindness. And here, we have the name of the ship for the first time in the poem—and it is as striking as it would be in a movie if we first saw the ship’s name in snow & ice & lashing sea, perhaps even lit by a flash and accompanied by thunder & the shrieks of the wind—The Deutschland! Later, in stanza 20, Hopkins will underscore the fitting ironies in the ship’s name—“O Deutschland, double a desperate name!” Of course, little did Hopkins know in 1875 how fitting, how prophetic his poem would be! But for now, for irrational arrogance, the ship is ‘hurling the haven behind.” And it goes into a world that is “unkind” . . .”black-backed” . . .”cursed quarter” . . .”widow-making unchilding unfathering deeps.”

The Deutschland plunges into the North Sea. The overall atmosphere, as at the beginning of Hamlet, is cold and unkindness. And here, we have the name of the ship for the first time in the poem—and it is as striking as it would be in a movie if we first saw the ship’s name in snow & ice & lashing sea, perhaps even lit by a flash and accompanied by thunder & the shrieks of the wind—The Deutschland! Later, in stanza 20, Hopkins will underscore the fitting ironies in the ship’s name—“O Deutschland, double a desperate name!” Of course, little did Hopkins know in 1875 how fitting, how prophetic his poem would be! But for now, for irrational arrogance, the ship is ‘hurling the haven behind.” And it goes into a world that is “unkind” . . .”black-backed” . . .”cursed quarter” . . .”widow-making unchilding unfathering deeps.” At this moment in the poem we see that Hopkins is as good a storyteller as Stephen King or as good a director as James Cameron or Peter Jackson: every word of the poem plunges, hurts, rips us and makes us have this experience of the voyage and shipwreck too.

In stanza 14, we can see the wreck on the sandbank: moreover, we can hear it, as if it had a soundtrack, with effects and music. And now the ship’s power is broken and she is helpless:

“And canvas and compass, the whorl and the wheel/Idle for ever to waft her or winde her with, these she endured.”

Stanza 15 is about hopelessness, as stanza 11 was about Death. And as the people try to climb into the rigging, “To the shrouds they took.” Again, I am reminded of those breathtakingly sublime images in Titanic, as the passengers try so near despair to climb up the last up-ended end of the mightily defeated ship!

And yet, for all these words of Death and Despair, even in the context of Despair, we hear, over and over, like a bell, ringing, singing, almost as if hear or overhear it, the knell of "Hope."

And yet, for all these words of Death and Despair, even in the context of Despair, we hear, over and over, like a bell, ringing, singing, almost as if hear or overhear it, the knell of "Hope." "Hope . . . Hope . . .Hope!"

The word "Hope" may alliterate with "hurling" and "horrible airs", but Hope is still sounding. And amidst this shipwreck, a great Hope is about to sound, the cry of the Tall Nun!

Into the snows she sweeps,

Hurling the haven behind,

The Deutschland, on Sunday; and so the sky keeps,

For the infinite air is unkind,

And the sea flint-flake, black-backed in the regular blow,

Sitting Eastnortheast, in cursed quarter, the wind;

Wiry and white-fiery and whirlwind-swivellèd snow

Spins to the widow-making unchilding unfathering deeps.

She drove in the dark to leeward,

She struck—not a reef or a rock

But the combs of a smother of sand: night drew her

Dead to the Kentish Knock;

And she beat the bank down with her bows and the ride of her keel:

The breakers rolled on her beam with ruinous shock;

And canvas and compass, the whorl and the wheel

Idle for ever to waft her or wind her with, these she endured.

Hope had grown grey hairs,

Hope had mourning on,

Trenched with tears, carved with cares,

Hope was twelve hours gone;

And frightful a nightfall folded rueful a day

Nor rescue, only rocket and lightship, shone,

And lives at last were washing away:

To the shrouds they took,—they shook in the hurling and horrible airs.

Yes, there is Hope to come!